Solving gossip-glomers distributed systems challenges: efficient broadcast 2 (part 3e)

Efficient Broadcast Challenge (Part II)

Here we are - the last part of the whole broadcast series. This is second part of the efficiency challenge, which builds

on the previous part. With the same node count of 25 and message delay of 100ms, the challenge is to achieve

the following performance metrics:

msgs-per-opshould be below20median latencyshould be below1secondmaximum latencyshould be below2seconds

In other words, we handled median and maximum latencies for lower messages per op during execution of the same workflow. Let me think for a moment…Since I can sacrifice latency in exchange for sending fewer messages, maybe it would be a good idea to batch messages before sending them and send them in the aforementioned batches?

Setup

Run these commands to bootstrap this part:

❯ mkdir broadcast-3e

broadcast-3e❯ go mod init github.com/deamondev/gossip-glomers-tutorial/broadcast-3e

❯ go work use ./broadcast-3e

Makefile

At this point you only should set MODULE to be broadcast-3e and WORKLOAD parameter to be broadcast-3e (see previous part

for the details).

Code

As I mentioned above, the whole idea is to add batching mechanism to our node. For doing so I’ll define new component which

I call batcher. Its whole role is just batching messages sent by our node to another nodes. The batcher has embedded ticker

which ticks every configured time duration. After tick, the batched messages are transformed into FlushEvent’s which are then

handled by the node internal handler.

broadcast-3e/batcher.go

package main

import (

"log"

"sync"

"time"

)

type Batcher struct { ⓿

mu sync.Mutex

batches map[string][]int

ticker *time.Ticker

flushChan chan FlushEvent

}

type FlushEvent struct { ❶

PeerID string

Messages []int

}

func NewBatcher(batchTimeout time.Duration) *Batcher { ❷

return &Batcher{

ticker: time.NewTicker(batchTimeout),

batches: make(map[string][]int),

flushChan: make(chan FlushEvent),

}

}

func (b *Batcher) Run() {

for range b.ticker.C {

b.mu.Lock()

for peerID, messages := range b.batches {

if len(messages) > 0 { ❸

b.flushChan <- FlushEvent{

PeerID: peerID,

Messages: messages,

}

}

}

b.batches = make(map[string][]int) ❹

b.mu.Unlock()

}

}

func (b *Batcher) Add(peerID string, message int) {

b.mu.Lock()

b.batches[peerID] = append(b.batches[peerID], message) ❺

b.mu.Unlock()

}

func (b *Batcher) Close() { ❻

log.Printf("Closing batcher")

b.ticker.Stop()

close(b.flushChan)

}

The Batcher struct ⓿ holds internal map of batched messages, where we batch array of messages (thst is, numbers)

per each peer id of the node in question. There is also ticker and channel of FlushEvent’s which is channel of

communication of the batcher with the external node (in which the batcher is embedded on).

The FlushEvent ❶ contains only info about the id of the peer and the batched messages. It is just plain data, which

is meant to be interpreted somehow in consumers of the flushChan channel. Such a separation of concerns is solid

design choice, since it is easier to reason and test the code.

In the constructor function ❷ we just configure the ticker via batchTimeout duration period - the intuition is that when

increasing this timeout, we minimize the msgs-per-op cluster characteristic and increase overall latency of the system

(and vice versa). I’ll summarize the experiments at the very end of this article.

The Run function is spawned as a separate goroutine in the node process and is supposed to work infinitedly.

After the (already configured) ticker ticks, we range all the peers of the node and for each of them we seek for

batched messages. For each of such a batch ❸, we send corresponding FlushEvent via flushChan channel. After that ceremony,

we clear batches for given peer ❹ and iterate.

The Add function ❺ is straighforward, we just append to array of batched messages.

The Close method ❻ is used to clear allocated resources, that is to stop the ticker and close flushChan channel.

Below is a diagram illustrating the described system:

broadcast-3e/server.go

In the server code I changed the semantics of internal broadcast messages being sent. That is, when the node’s handler of sending actual batched messages sends them to the dest node, it’ll send it via internal broadcast message. Hence, the current definition is:

type BroadcastInternalMessage struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

Messages []int `json:"messages"`

}

I also need to adjust NewServer method in order to spawn batcher and inject it into the node structure:

type Server struct {

node *maelstrom.Node

nodeID string

mu sync.Mutex

messages map[int]struct{}

topology map[string][]string

masterNode string

role string

batcher *Batcher

}

func NewServer(n *maelstrom.Node) *Server {

b := NewBatcher(200 * time.Millisecond)

s := &Server{node: n, messages: make(map[int]struct{}), batcher: b}

//Rest of the code in this method remains the same as in broadcast-3d challenge solution.

}

The mentioned FlushEvent’s handler definition is:

func (s *Server) handleFlushes() {

for event := range s.batcher.flushChan {

msg := BroadcastInternalMessage{

Type: "broadcast_internal",

Messages: event.Messages,

}

go broadcastMessageToPeer(s.node, event.PeerID, msg)

}

}

I think it should be self-explanatory - for every FlushEvent we send batched messages to proper peer via broadcast_internal message.

The other two places where the code is changed are two handlers:

func (s *Server) broadcastHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

var body BroadcastMessage

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// To avoid cycles: n0->n1->n2->n0

if _, exists := s.messages[body.Message]; exists {

broadcastMessageResponse := BroadcastMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastMessageResponse)

}

s.messages[body.Message] = struct{}{}

for _, peerID := range s.topology[s.nodeID] {

s.batcher.Add(peerID, body.Message)

}

if s.role == "FOLLOWER" {

// Broadcast to the master node

s.batcher.Add(s.masterNode, body.Message) ⓿

}

broadcastMessageResponse := BroadcastMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastMessageResponse)

}

func (s *Server) broadcastInternalHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

var body BroadcastInternalMessage

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

var unseenMessages []int ❶

for _, m := range body.Messages {

if _, exists := s.messages[m]; !exists {

unseenMessages = append(unseenMessages, m)

s.messages[m] = struct{}{}

}

}

if len(unseenMessages) == 0 {

broadcastInternalMessageResponse := BroadcastInternalMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_internal_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastInternalMessageResponse)

}

for _, m := range unseenMessages {

for _, peerID := range s.topology[s.nodeID] {

s.batcher.Add(peerID, m) ⓿

}

}

broadcastInternalMessageResponse := BroadcastInternalMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_internal_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastInternalMessageResponse)

}

There are two effective changes:

- ⓿ - instead of sending an internal broadcast message we perform batching via

batcher’sAddmethod. - ❶ - since

broadcast_internalmessage ships a whole bunch of messages (batch), we need to decide which of them were already seen by our node. This is direct generalization of a previous solution, where we just got one message.

The last part of server code is:

func (s *Server) Run() error {

go s.handleFlushes()

go s.batcher.Run()

return s.node.Run()

}

func (s *Server) Close() {

log.Printf("Closing server")

s.batcher.Close()

}

These methods are straightforward to grasp on, instead of explaining direct code, let me show you the changes in main.go file.

broadcast-3e/main.go

We didn’t touch that entry file for a long, long time. Since we now need to take care of resources, this looks as follows:

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

maelstrom "github.com/jepsen-io/maelstrom/demo/go"

)

func main() {

log.SetOutput(os.Stderr)

n := maelstrom.NewNode()

s := NewServer(n)

defer s.Close()

if err := s.Run(); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Running workload

Let us see if messages propagate in the cluster properly:

❯ make run

go build -o ~/go/bin/maelstrom-broadcast-3e ./broadcast-3e

INFO [2026-01-31 19:36:11,933] jepsen node n0 - maelstrom.net Shutting down Maelstrom network

INFO [2026-01-31 19:36:11,934] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core Analyzing...

INFO [2026-01-31 19:36:12,398] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core Analysis complete

INFO [2026-01-31 19:36:12,421] jepsen results - jepsen.store Wrote /home/deamondev/software_development/tutorials/gossip-glomers-tutorial/store/broadcast/20260131T193538.965+0100/results.edn

INFO [2026-01-31 19:36:12,441] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core {:perf {:latency-graph {:valid? true},

:rate-graph {:valid? true},

:valid? true},

:timeline {:valid? true},

:exceptions {:valid? true},

:stats {:valid? true,

:count 2000,

:ok-count 2000,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0,

:by-f {:broadcast {:valid? true,

:count 1001,

:ok-count 1001,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0},

:read {:valid? true,

:count 999,

:ok-count 999,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0}}},

:availability {:valid? true, :ok-fraction 1.0},

:net {:all {:send-count 10882,

:recv-count 10882,

:msg-count 10882,

:msgs-per-op 5.441},

:clients {:send-count 4100, :recv-count 4100, :msg-count 4100},

:servers {:send-count 6782,

:recv-count 6782,

:msg-count 6782,

:msgs-per-op 3.391},

:valid? true},

:workload {:worst-stale ({:element 259,

...

993

995

996

997

998),

:never-read-count 0,

:stable-latencies {0 0,

0.5 738,

0.95 891,

0.99 977,

1 993},

:attempt-count 1001,

:never-read (),

:duplicated {}},

:valid? true}

Everything looks good! ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

We did it! Now the msgs-per-op is 5.441 which is much below 20. Our stable latencies also satisfy requiremnents.

Summary

We have reached the end of our adventure. I hope that my solutions will help someone else in solving an intriguing gossip glomers challenge. Feel free to gossip about these solutions with your friends!

Appendix – Impact of batch timeout parameter on cluster’s characteristics

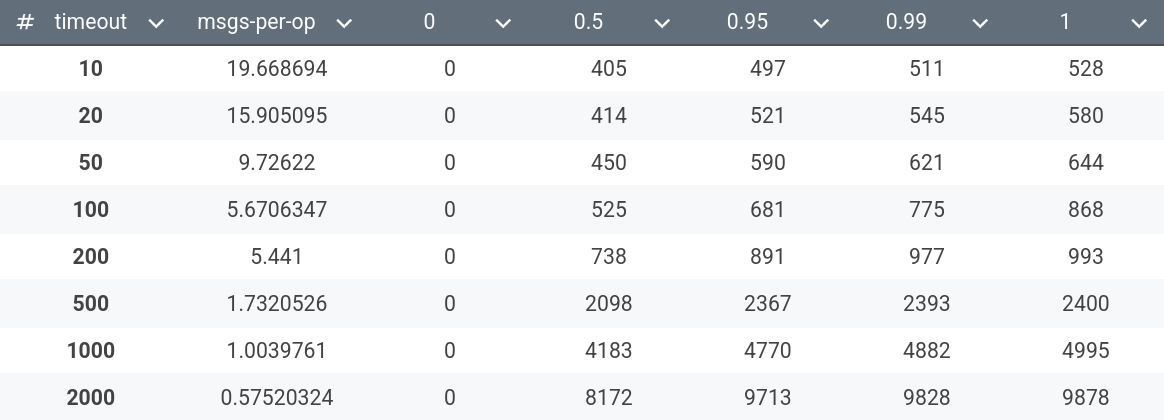

Here I show the table which shows the impact of batchTimeout parameter on the characteristics in question:

It looks like stable-latency behaves as \(x \mapsto kx+b \) for \(k \approx 4.1\) and \(b \approx 365\). Of course, this is only a heuristic.

.svg)