Solving gossip-glomers distributed systems challenges: efficient broadcast 1 (part 3d)

Efficient Broadcast Challenge (Part I)

Things are getting interesting! This is the first part of the efficiency challenge, which builds on the fault-tolerant broadcast challenge. The workload is becoming more rigorous:

- node count is increased to

25 - there is

100msdelay to each message to simulate slow network

Our challenge is to achieve:

msgs-per-opshould be below30median latencyshould be below400msmaximum latencyshould be below600ms

Remark. We should still ignore the topology proposed by maelstrom, since it is just 2 dimensional grid of nodes. Such a topology duplicates a lot of messages and add latencies of order \(2 \cdot \sqrt n\). In fact, we may simply remove some connections from such a grid to improve its characteristics. I will investigate this further in the corresponding topology section of this article.

Setup

Run these commands to bootstrap this part:

❯ mkdir broadcast-3d

broadcast-3d❯ go mod init github.com/deamondev/gossip-glomers-tutorial/broadcast-3d

❯ go work use ./broadcast-3d

Makefile

Let’s calibrate MODULE to broadcast-3d and WORKLOAD parameter to broadcast-3de (since we’ll reuse it in last part).

Our new maelstrom command should be:

MAELSTROM_CMD_broadcast-3de = maelstrom/maelstrom test -w broadcast --bin $(BINARY) --node-count 25 --time-limit 20 --rate 100 --latency 100

Code

That time we create new file with our custom topology:

broadcast-3d/topology.go

package main

var topology = map[string][]string{

"n0": {},

"n1": {"n0"},

"n2": {"n1", "n3"},

"n3": {"n4"},

"n4": {},

"n5": {},

"n6": {"n5"},

"n7": {"n6", "n2", "n8"},

"n8": {"n9"},

"n9": {},

"n10": {},

"n11": {"n10"},

"n12": {"n7", "n11", "n13", "n17"},

"n13": {"n14"},

"n14": {},

"n15": {},

"n16": {"n15"},

"n17": {"n16", "n18", "n22"},

"n18": {"n19"},

"n19": {},

"n20": {},

"n21": {"n20"},

"n22": {"n21", "n23"},

"n23": {"n24"},

"n24": {},

}

// It is hardcoded, in a real system it should be dynamic

var masterNode = "n12"

The idea behind that is we simply remove all the vertical arrows from full 2d grid topology. Thanks to central place of n12 node,

by routing through it we see that we may reach any node from any node in at most 5 steps. For example, reaching n4 from n21 is just

sequence of steps: n21-->n12-->n7-->n2-->n3-->n4. This is true in general, since any node from n12 is reachable within at most 4 steps.

We declare n12 to be master node, altough maybe better name might be central node?

Why do I think that subgraph of full 5x5 grid is kinda special? Denote by \(G\) the full \(5\times 5\) grid graph and let \(H\subseteq G\) be any (directed) subgraph of \(G\). For any given vertex \(v \in H\) let \(\operatorname{deg}^+(v)\) be the number of outgoing edges from \(v\). Let us also take any convex function \(f : \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). We’re interested on the class of directed subgraphs of \(G\) which contain every vertex of \(G\) and for which there exists central node - that is a node for which the distance from every other node is \(\leq 5\). For any such subgraph \(H\) we take vector of numbers

\[ \vec{v}(H) := (\operatorname{deg}^+(v_1), \dots, \operatorname{deg}^+(v_{25})) \in \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 25} \]My claim is that the spanning tree rooted at the grid center minimizes the number:

\[\sum_{k=1}^{25} f(\operatorname{deg}^+(v_k))\]For every convex function. In case \(f \colon x \mapsto x^2 \) then this number is just square length of vector \(\vec{v}(H)\) in \(\mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 25}\). So our chosen subgraph above is unique (up to grid automorphism) and minimizes these functionals. Using standard combinatorial notation, our vector is as follows:

\[(4^1,3^2,2^2,1^{10},0^{10})\]Hence, its length squared is:

\[ 1\cdot 4^2+2\cdot 3^2+2\cdot 2^2+10\cdot 1^2+10\cdot 0^2 = 52\]The proof is rather straightforward. Dividing the full grid into chunks and analyzing we need at least one node with outgoing degree 4. Then analyzing that we need at least two outgoing degree 3 nodes (if we demanded less, then at least an additional one 4 out-degree would need to exist which by function concativity increase the number in question) and so on… Of course the devil lives in details.

broadcast-3d/server.go

I think at this moment the ideas are being condensed to the point I would rather like to split out server code into more easily explainable chunks. In first such a chunk I will explain how we handle topology in nodes.

type Server struct {

node *maelstrom.Node

nodeID string

mu sync.Mutex

messages map[int]struct{}

topology map[string][]string

masterNode string ⓿

role string ❶

}

func (s *Server) topologyHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

var body TopologyMessage

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// We ignore topology sent from maelstrom's controller, at least for now

topologyMessageResponse := TopologyMessageResponse{

Type: "topology_ok",

}

log.Printf("Received topology information from controller: %v", body.Topology)

s.topology = topology

s.masterNode = masterNode

log.Printf("Using topology: %v, central node: %s", s.topology, s.masterNode)

if s.nodeID == masterNode { ❷

s.role = "LEADER"

} else {

s.role = "FOLLOWER"

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, topologyMessageResponse)

}

To our Server struct I added new two fields:

masterNode⓿ - who is master node in the cluster?role❶ - am I leader or follower in the cluster?

I also set topology to be the hardcoded one which I already presented. The determination of the role is just

simple check ❷ whether node id is equal to the (hardcoded) master node id.

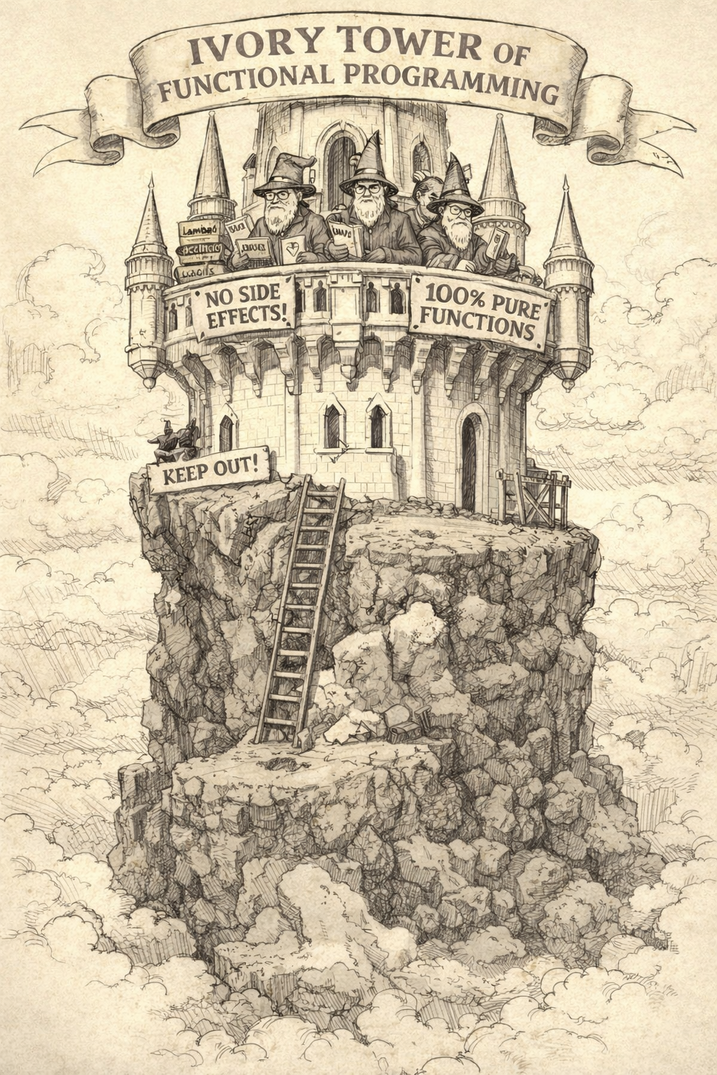

Aside note from the ivory tower of functional programming

Welcome brave ones! After reading this article, our council decided to take the floor and explain why we THINK that functional languages are BETTER SUITED to building complex distributed systems….

After careful thought I decided to skip the letter from mages and just present my own take. I promised myself I would finish with academy, and I’d better stick to it.

I think this is the right place to share my thoughts on why I would not choose Go for writing a complex distributed system.

Much as I like Go for its ability to compile into a statically linked binary and its excellent standard library, I think

its type system is too weak. Recall two new fields I described above, that is masterNode and role fields. What if we would

like to support some kind of operation which should be performed only on leader? With the current implementation, the aforementioned

code would like like this:

func (s *Server) someLeaderOnlyFoo() error {

if s.role == "FOLLOWER" {

return errors.New("That operation should be invoked only on LEADER, but it was invoked on FOLLOWER")

} else {

// perform actual job...

// ...

return nil

}

}

I think you know what I mean? There is a slogan, quite popular in the world of functional programming which is make illegal states unrepresentable. The situation is even more problematic because many distributed systems introduce new roles. An example of this is ZooKeeper’s observer role or etcd’s learner role.

Let me present how we might model it in languages with stronger type system. What about java and rust?

Java’s take

In modern Java, by which I mean 17+ one can use sealed interfaces to model server role without holding internal state variable.

public sealed interface Server

permits LeaderServer, FollowerServer {

String nodeId();

}

public final class LeaderServer implements Server {

private final String nodeId;

public LeaderServer(String nodeId) {

this.nodeId = nodeId;

}

@Override

public String nodeId() {

return nodeId;

}

public void someLeaderOnlyFoo() {

// actual job

}

}

public final class FollowerServer implements Server {

private final String nodeId;

public FollowerServer(String nodeId) {

this.nodeId = nodeId;

}

@Override

public String nodeId() {

return nodeId;

}

}

What we gained? There are some gains

- follower is not able to invoke leader-only methods

- exhaustive compile time checks

- clear domain model

Of course we may still get this in golang (if we loosen the interface being sealed and exhaustiveness of switch expressions). But the thing is - it is not idiomatic go then. In my impression go is closer in style to C language. I have to admit such a minmalism of go has some kind of a charm and I like it when writing ops kind of software, cli tools, terminal UIs, … For complex backend systems? Definiely too weak type system for me. Sorry.

But who cares what I prefer, anyway?

Rust’s take

What about going even further and take an advantage of rust’s move semantics in the incarnation of typestate pattern?

struct Leader;

struct Follower;

struct Server<State> {

node_id: String,

_state: std::marker::PhantomData<State>,

}

impl Server<Follower> {

fn new_follower(node_id: String) -> Self {

Server {

node_id,

_state: std::marker::PhantomData,

}

}

fn promote(self) -> Server<Leader> {

Server {

node_id: self.node_id,

_state: std::marker::PhantomData,

}

}

}

impl Server<Leader> {

fn some_leader_only_foo(&self) {

// actual job

}

fn demote(self) -> Server<Follower> {

Server {

node_id: self.node_id,

_state: std::marker::PhantomData,

}

}

}

Here I define two roles: Leader and Follower. These are just marker types.

The generic Server just holds common data - the id of the node and phantom type _state to track

the server’s role at the type level. Note that one is not able to create Leader from the void.

It may be created only by promoting Follower via Follower’s promote method.

But wait. I can define the same in Java, probably after fighting with type erasure for a while.

You’re correct then. But there is more. Consider this code snippet:

let follower = Server::new_follower("n1".to_string());

let leader = follower.promote(); // follower is moved, cannot use anymore

// follower.some_method() -> COMPILE ERROR

Since Rust’s type system is affine by default and enforces move semantics it ensures that old states cannot be reused after a transition. In Java the original variable would still exists and could be used after the method call. The compiler does not prevent misuse. You could accidentally call a “follower-only” method on what conceptually is no longer a follower.

Conclusion of the letter

In conclusion, I would like to state that I do not believe the main problems in distributed systems are caused by better or worse domain modelling. In practice, the main challenges arise from handling partial failures, retries, timeouts, recovery and the discrepancy between local correctness and the behaviour of the global system.

Let us come back to the more imperative earth…

type BroadcastMessage struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

Message int `json:"message"`

}

type BroadcastMessageResponse struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

}

type BroadcastInternalMessage struct { ⓿

Type string `json:"type"`

Message int `json:"message"`

}

type BroadcastInternalMessageResponse struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

}

type ReadMessage struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

}

type TopologyMessage struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

Topology map[string][]string `json:"topology"`

}

type TopologyMessageResponse struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

}

type ReadMessageResponse struct {

Type string `json:"type"`

Messages []int `json:"messages"`

}

I introduce a new type of message being passed from our nodes to other nodes which is internal broadcast message ⓿. The rest of the messages remains the same.

func (s *Server) broadcastHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

var body BroadcastMessage

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// To avoid cycles: n0->n1->n2->n0

if _, exists := s.messages[body.Message]; exists {

broadcastMessageResponse := BroadcastMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastMessageResponse)

}

s.messages[body.Message] = struct{}{}

broadcastInternalMessage := BroadcastInternalMessage{

Type: "broadcast_internal",

Message: body.Message,

}

for _, peerID := range s.topology[s.nodeID] {

go broadcastMessageToPeer(s.node, peerID, broadcastInternalMessage) ⓿

}

if s.role == "FOLLOWER" { ❶

// Broadcast to the master node

go broadcastMessageToPeer(s.node, s.masterNode, broadcastInternalMessage)

}

broadcastMessageResponse := BroadcastMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastMessageResponse)

}

func (s *Server) broadcastInternalHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

var body BroadcastInternalMessage

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// To avoid cycles: n0->n1->n2->n0

if _, exists := s.messages[body.Message]; exists {

broadcastInternalMessageResponse := BroadcastInternalMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_internal_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastInternalMessageResponse)

}

s.messages[body.Message] = struct{}{}

// To avoid: n0->n0

for _, peerID := range s.topology[s.nodeID] {

go broadcastMessageToPeer(s.node, peerID, body)

}

broadcastInternalMessageResponse := BroadcastInternalMessageResponse{

Type: "broadcast_internal_ok",

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, broadcastInternalMessageResponse)

}

Dragons be here. As I already mentioned above, to solve this challenge I’ve introduced new message type which is

internal_broadcast message. When the node receives this kind of message, then the node just propagates this message

to its peers without any other logic. Plain and easy. I introduced this new kind of message because adding too much

logic in broadcast message is not a good idea by the reason the broadcast messages are also sent from controller

nodes to nodes. When trying to accumulate too much logic into message which we dont control ourselves, the code is

becoming harder and harder to conceptualize, since it has different semantics depending on who called the message.

What about

broadcastthen and why exactly we need this new message?

The whole logic sits in broadcast message handler. As before we check if our node already saw message. In the

interesting case when the message is seen by the very first time, the first thing the node is doing is sending

internal broadcast messages to all its peers ⓿. So the messages start propagating on the grid in some places. Then,

the node checks if it is a follower of the cluster ❶. If it is then it realizes its peers are not enough to broadcast

message to whole cluster. So what is the natural thing to do? Drums rolling… I think you’ve got it, it just sends

internal broadcast message to the master (central) node n12 ❷. Then we have a guarantee message eventually converges

everywhere. In fact it would suffice to just re-transmit a message to master node, and this first step of sending internal

broadcast messages to the node’s peers is kind of an optimization.

Below I paste the visual representation of the case in which controller sends broadcast message to follower node.

It shows how the internal_broadcast messages flows:

Running workload

Let us see if messages propagate in the cluster properly:

❯ make run

go build -o ~/go/bin/maelstrom-broadcast-3d ./broadcast-3d

...

INFO [2026-01-12 15:32:44,575] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core Analyzing...

INFO [2026-01-12 15:32:45,050] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core Analysis complete

INFO [2026-01-12 15:32:45,074] jepsen results - jepsen.store Wrote /home/deamondev/software_development/tutorials/gossip-glomers-tutorial/store/broadcast/20260112T153211.516+0100/results.edn

INFO [2026-01-12 15:32:45,100] jepsen test runner - jepsen.core {:perf {:latency-graph {:valid? true},

:rate-graph {:valid? true},

:valid? true},

:timeline {:valid? true},

:exceptions {:valid? true},

:stats {:valid? true,

:count 1978,

:ok-count 1978,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0,

:by-f {:broadcast {:valid? true,

:count 999,

:ok-count 999,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0},

:read {:valid? true,

:count 979,

:ok-count 979,

:fail-count 0,

:info-count 0}}},

:availability {:valid? true, :ok-fraction 1.0},

:net {:all {:send-count 53940,

:recv-count 53940,

:msg-count 53940,

:msgs-per-op 27.26997},

:clients {:send-count 4056, :recv-count 4056, :msg-count 4056},

:servers {:send-count 49884,

:recv-count 49884,

:msg-count 49884,

:msgs-per-op 25.219414},

:valid? true},

...

:lost (),

:stable-count 999,

:stale-count 995,

:stale (0

1

2

3

4

5

...

993

994),

:never-read-count 0,

:stable-latencies {0 0,

0.5 379,

0.95 478,

0.99 494,

1 498},

:attempt-count 999,

:never-read (),

:duplicated {}},

:valid? true}

Everything looks good! ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

It seems we’re good. The msgs-per-op is 27.26997 which not exceeds 30. Median latency id 379 which is below 400 and

max latency is 498 which is below 600.

Summary

As you can see, optimising the code required effort on our part. At this point, we could feel that we were actually solving the problems of a distributed system. The final stage of our journey lay ahead of us.